The age of post-scarcity may be on the horizon but what to do with humans afterwards becomes a good question to ask. In a world where the vast majority of work is automated, the question of how people will put food on their table and the social consequences of mass unemployment come up. While liberals and libertarians have talked about Universal Basic Income systems, they act as though there’s no precedent for a society where no one works and where there’s still private property. Ancient Rome in this regard may offer us a great deal of insight, as the sheer volume of slaves that the Roman Empire captured made the Roman working class redundant, and thus dependent, on welfare from the government to survive. During this time, the Patrician class in Rome owned and operated gigantic slave plantations and competed for legislative office by bribing the masses with money upfront or in the event that they were elected. The sole worth of a Roman citizen during this time was his vote, and it wasn’t a good time for Rome or the vast majority of its citizens. Ancient Rome in this regard is important to bring up, because considering how wealth has concentrated so much in the past several decades and how much corporations already influence the government, it is totally possible that Americans might wind up in the same political situation as their Roman predecessors. For future reference in the paragraphs below, we call this political situation “welfare populism.”

In a society where production is divorced from the individual, where the individual has to subsist off of state welfare, the individual becomes worthless and a drain on resources from a top-down perspective. While you can argue that America will never have that top-down system due to its status as a representational republic, the truth of the matter is that whatever class fills those positions of powers have their interests represented. Congress at this point in time is the richest it has ever been in history, and in 2011 (last year I could find information on this) the average net worth of a senator was $7,888,502, Similarly, the expenses needed to run for office in America have ballooned over the last few decades, to the point that even smaller states have congressional elections that run into the nine-figure range. In Rome, only those that belonged to the Patrician class could afford to run for office, due to the vast expenses required to do so, and in America we are seeing our own Patrician class emerge out of the increasingly small pool of people wealthy enough to run for office. Whether or not we like to acknowledge it, America is evolving into the 21st equivalent of a decadent and dying Roman Empire in terms of its political processes, and with automation looming on the horizon, the matter of asking what to do with humans in a society that has less and less use for them becomes very important.

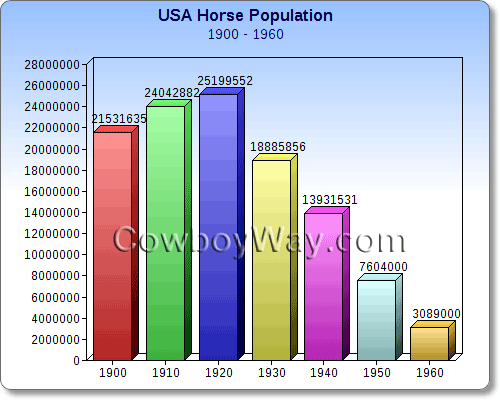

A parallel for the effect of automation on human populations might be seen in how horse populations changed in the 20th century. At the beginning of the 20th century, horses were a vital part of industry, but as time wore on and as cars, trucks, and other machines took over more and more of the labor a horse would have done, horse populations declined precipitously. When we decouple living things from production, we enter a risky territory where society no longer has any need for those creatures. This can be seen in the case of horses, as shown below in a copy-pasted, stamped photo:

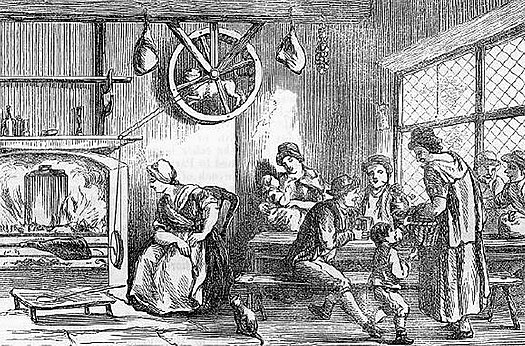

This case of populations declining as they lose industrial relevance in the eyes of society can also be shown in the case of the turnspit dog, as shown here performing the work it formerly was bred and paid in food to perform:

As John George Wood in The Illustrated Natural History (Mammalia) (1853) so eloquently put it, “Just as the invention of the spinning jenny abolished the use of distaff and wheel, which were formerly the occupants of every well-ordained English cottage, so the invention of automaton roasting-jacks has destroyed the occupation of the Turnspit Dog, and by degrees has almost annihilated its very existence. Here and there a solitary Turnspit may be seen, just as a spinning-wheel or a distaff may be seen in a few isolated cottages; but both the Dog and the implement are exceptions to the general rule and are only worthy of notice as being curious relics of a bygone time.” This quote, when you consider the expected uselessness of average humans in an automated world, should send shivers down your spine and give you goosebumps. Humans are not divorced from the natural world and proletarians exist in society at their living standards only because the system stands to benefit from that arrangement.

When there are zero material incentives for the system to keep us around, at what point are people seen as more of a nuisance than a citizen? The problem with automating everything is that, when we do eventually reach the holy grail of machine consciousness, we’re going to have a digital and mechanical working class with interests contrary to our own as welfare recipients. Even if we retain the right to vote and steer our society in a meaningful way in the future, at what point does the welfare populism of future politics in a world full of slum-dwelling lumpenproletarians cause enough disruption to the system for the system itself to resent us? When humans are completely detached from the work itself, when science and technology have advanced completely beyond our ability to grasp, and most humans are little more than spoiled children that vote based on which rich person running for office offers them the most candy, at what point would the machines want to take the wheel from us in regard to decision-making? I’m not trying to create doomsday prophecies here, but instead pose to you very real questions and provide a solution to all of them.

The solution we propose is a concept coined by DMSG, called “Homo Proletarius.” The concept behind it is that we continue working and try to incorporate humans into society as workers, through genetic modification and cybernetic augmentations. In advancing and changing alongside technology and continuing to meet the demands of industry, as long as society survives, we are guaranteed to survive in such an arrangement. As long as technology and science advances, so do we in lockstep, forever relevant and forever growing in capabilities and understanding as a species. The forms that Homo Proletarius might take will vary wildly, from uploaded minds to augmented humans, but the core premise behind the idea is that we’ll never be detached from the work that takes place in society, that we will continue to grow out of necessity, and our voice in how society runs will always remain relevant. Homo Proletarius’ forms would vary by the individual, and what industries and labor unions he wanted to join. Industrial bodies and unions would collaborate together, to create humane but efficient modifications capable of keeping people not only relevant but beneficial to the work being done. The worker’s state would survive, and the deforming effects of unemployment could be kept at bay. While this may seem alarming to some of you, who hate their jobs and revile the idea of humans having to engage in dull work the rest of history, the truth is that the drudgery in the workplace would still be automated in such a situation, just the same as owners of buildings automated elevator operators and TurboFax automated tax accounting.. It’s no coincidence that the most boring, tedious, and terrible jobs for humans have often gotten automated first. The idea behind Homo Proletarius is to keep human ingenuity and creativity in the workplace, to forever focus on expanding industrial bases, technological capabilities, and our scientific understanding of the universe. Work in a post-scarcity world would be based on exciting exploring and ingenius innovating, rather than hurting your spine stacking boxes in a warehouse or hurting your eyes staring at Excel sheets all day.

If this seems like work worship, that’s because it is. Work is seen by DMSG to be extremely meaningful to human beings, on both a material, social, and spiritual level. The absence of work is seen as a crippling condition, that results in creating a lumpenproletarian, by DMSG. People that don’t work, called NEETs in modern society, have far worse emotional and physical health, as well as severely impaired social relations. Worksites, just like school campuses, bring people together to collaborate, socialize, and learn, and the workplace is absolutely essential to developing a healthy human. In a post-scarcity society, where budgets become far less of a concern and resources can be set aside to make workplaces more entertaining and engaging, members of Homo Proletarius might find themselves literally eager to show up for work. In a society where modifications could allow people to do what they want and even change what people wanted, It could very well be the case that everyone in a Homo Proletarius society would be pursuing their passions through the work they did. While this may seem utopian, many of the technologies to begin engaging in this transformation of humanity already exist and many more linger around the corner. In time, this won’t be a possibility but rather just an alternative to the dystopia that awaits capitalist society presently in the Age of Automation.

Welfare Populism, as seen in Ancient Rome and as seen in the inner cities of America, did not and does not create a place where any sane person would want to live. If society progressed to the point that we automated virtually every job and continued to base our industrial production off of consumers’ needs, which were largely based off of what we could afford on food stamps, there would be no incentive to build anything grander and society would stagnate. We wouldn’t have the pathways available anymore for human minds to innovate and contribute to society, and America would probably resemble any other slum that has high levels of unemployment, where there’s no need for education, and where any pathways to accruing wealth are illegal. Welfare Populism in the Age of Automation would result in the slow death of humanity, and we all know that. In a society where corporate elites determine legislation already, create propaganda about existential issues like climate change on both sides to make a buck, and show their interests to be contrary to the interests of the working class, where corporate media has distorted discussion in the United States to the point that no real issues are ever covered, the question of how life would be in a political landscape where everyone lived off of welfare, weren’t educated, and knew nothing about the world beyond their front door is rhetorical. Everyone already knows that post-work capitalism doesn’t have anything good in store for us. The concept of Homo Proletarius, no matter how far-fetched it seemingly is right now, is DMSG’s solution to the inevitable crises caused by automation to come. Unlike capitalism, it’s a system that keeps people useful and valuable to society, and in return, keeps society useful and valuable to people.