When historians look back at Chimerica, it may be one of the clearest cases in history where the bourgeois from opposite sides of the spectrum aligned together, in order to engage in trade to their mutual benefit. In 1971, China was pathetic and weak, a sickly country with an enormous but hungry population, with enemies in the communist circle of countries that refused to cooperate with it. Mao Zedong, who had been helped greatly by the Soviet Union in taking power in China, had wanted China to be the leader of the socialist world, believing that as the country with the largest population, China was the true epicenter of socialist thought. China, after the death of Stalin, distanced itself from the Eastern Bloc, aligning with outcasts like Hoxha in their attempt to usurp Eastern Europe as the center of socialist thought, but due to China’s industrial and technical inadequacies, no one took China seriously. China’s greatest battle internationally at the time was trying to escape the shadow cast by the enormously powerful Soviet Union, and China on its own was incapable of this. The United States saw an opportunity in China, in being able to pull apart the communist camp, and in being able to disrupt the stranglehold that unions held over the American economy. In 1971, Sino-American relations were formalized, ushering in an age of outsourcing, offshoring, intellectual property theft, Chinese suicide nets, and the deindustrialization of the American labor force. The formation of Chimerica began with the two sides seeing opportunities to gain in one another, and only now is fracturing as the two countries come to realize that the global stage isn’t big enough for both of them. In this article, we’re going to look at how China and America came to see each other as allies, and how that relationship has fractured in the years since.

During Mao’s reign in China, the totalitarian country was in tatters having been ravaged again and again by the lunacy of the Chinese Communist Party. Mao’s paranoia, as well as his grand designs, subjugated the country’s industries and its populaces to incredibly whimsical, and oftentimes very harmful, demands. China, having been a massive country ravaged by war between the Chinese nationalists and the Japanese Empire, had hardly recovered before Mao put into place hardline Stalinist measures, killing millions in Mao’s quest to catch China up with the rest of the world by trying to industrialize the country. While Stalin’s personality cult was wielded as a tool by the Soviet Union’s communist party, a tool that Stalin often derided for its ridiculousness, Mao’s personality cult was a function of not only the government in China at the time but also the best way to cement Mao’s position within his regime. While personality cults in the Soviet Union were designed to unite people that may not have typically agreed with the political party’s values, in China the personality cults created by the communist party there were intended to eliminate factionalism, giving the premier dictatorial powers. In the Soviet Union, the things that existed there largely existed due to utility and function alone, as was reflected in the endless amounts of generic acronyms that permeated Soviet Culture, as was evidenced in the endless cities of grey buildings erected within months, and so. Under Mao Zedong’s reign, much of what existed in China only existed because it helped Mao to retain his power and cement his rule. While Stalin lead the communist party in the Soviet Union, his position was at best described as that of a team captain, rather than a boss, due to the fact that the power he obtained was within the constraints of what the Soviet bureaucracies would allow. In China, due to the fact that the Soviet Union had built up a personality cult around Mao in order to hasten the revolution there, Mao had far more power than Stalin did in his own regime and after the revolution, his material interests demanded that he focus on retaining that power at any cost. Stalin was not the government in the Soviet Union, while Mao very much was the government in China.

Another defining difference in how the Soviet Union and China approached the Developed World was that, for the most part, the industries that Tsarist Russia had left in the Soviet’s hands were a bit more developed than their Chinese counterparts. Due to the fact that the Soviet Union was completely isolated from the rest of the world politically in its nascent days, not having the luxuries of aligned states that China later on had, the USSR used the sale of its grains to buy industrial equipment and develop their means of production by participating in the global market. The USSR also regularly brought over Western workers and companies, in order to develop their means of production and train their workforce. Despite being a poor country initially, the USSR was able to rapidly advance because its bureaucrats saw the advantages that came with friendliness. When Mao’s China emerged on the scene in the late 1940’s, the socialist camp already had numerous states more than happy to engage in non-profit, mutually beneficial trade. Mao didn’t do this, rejecting the Eurasian-centrism of the existing socialist camp, feeling that by virtue of population alone, China was entitled to lead the world forward into socialism. Putting it into perspective, that’d be similar to modern India demanding to lead the “democratic” capitalist world, due to their population, happily alienating any and all potential allies in Modi’s quest for glory. The defining problem in this rationale was that Mao wanted to be a world leader, in a time when China simply couldn’t be. Stalin, by virtue of the USSR being the sole socialist state for decades, was the world leader of socialism from the start, and that was less out of desire and more out of simple circumstances. China was severely hindered by Mao’s megalomania, because unlike in the Soviet systems where the political elite still had to get some semblance of consent from one another and the bureaus underneath them, in China this system of technocratic dialogue never developed. Due to the simple fact that Mao’s personality cult formed the bulk of the governance style in China’s revolutionary period, there was zero interest from the top to change that once Mao took power, as everyone at the top were already the most successful sycophants of Mao. Everything China did was what Mao wanted, with people being routinely executed for trivial things, while in the Soviet Union, a 38-year-old filmmaker was caught sleeping with Stalin’s 16-year-old daughter and went to a labor camp for a decade over it. While the punishment for the sexual predator isn’t light, the fact that someone could engage in statutory rape with the supposed dictator’s daughter and survive sheds a lot of light on how the Soviet Union operated, showing that unlike what capitalist propaganda would have you believe, people weren’t dying left and right on a whim at the hands of a dictator. It’s safe to say that Stalin wanted to kill that perverted filmmaker; it’s more important to note that the filmmaker was unharmed.

The Great Leap Forward, a campaign in China to rapidly modernize the country, showed the unbridled brutality that the CCP was willing to engage, as well as the futility of putting isolationist, largely uneducated politicians in charge of the economy. After the travesties of the Great Leap Forward in China, under which their inept communist party caused the country stumble into a succession of punishing famines and economic collapses, Mao’s image was weakened greatly, and his potential usurpers had begun circling him like hungry sharks. Blood was in the water, and while it was the blood of the tens of millions that had lost their lives due to Beijing’s poor policies, Mao had begun to fear that he’d be added to that number if he didn’t think of something soon. Mao began the Cultural Revolution in China, using the intangible nature of culture to more easily single out his political opposition as traitors and other sorts of deviants, using the vast campaign as a cover to once again cement his rule. During the Cultural Revolution in China, vigorously pro-Mao students began to form student groups, with the first one forming at a middle school in Beijing – perhaps unsurprisingly – that called itself “red guards who defend Mao Zedong thought.” Mao gave his blessings to this group, empowering more and more of these fanatical student groups to burn down temples, political enemies, and often innocent people, fanning the flames of their destructive glee to purge his opposition and ensure his rule went unchallenged in the Chinese Communist Party. Mao had made the students, the intelligentsia of China, the stewards of the Cultural Revolution, giving the mobs the leniency and power to carry out the Cultural Revolution in ways that even the state didn’t want to officially touch. The students formed what would come to be known as Red Guard groups, with the different factions beginning to fight violently with one another over who was the most Maoist, in what is one of the more retarded examples of leftist infighting. This infighting peaked in the summer of 1968 at Tsinghua University, where two oppositional cadres engaged in what became known as the Hundred Day War, where the groups hurled stones, spears, and sulphuric acid at each other in their fight to prove who loved Mao the most. These skirmishes got so out of hand that over half the university students fled, forcing Mao to put an end to the conflict as his personality cult’s most fanatical believers began to make larger and more embarrassing fools of themselves and subsequently, him.

In late July, Mao decided to utilize the Chinese proletariat quite literally as a human shield. Organizing a group of 30,000 factory workers known as the “Capital Worker Mao Zedong Thought Propaganda Teams,” the group went to Tsinghua University on July 27th, 1968, and tried to put themselves between the two rival Red Guard groups on campus, with the aim being to disrupt and end the infighting. The resulting clashes resulted in the deaths of six workers and the injuring of over 700 workers, causing Mao to disband the Red Guards the next day. Unofficially, the workers most likely went there and just beat the shit out of the Red Guard students on behalf of Mao. Within a week of the disbanding the Red Guards, Mao sent a re-gifted package of Mangos he didn’t want, given to him by a Pakistani diplomat, to the factory workers who were still stationed at Tsinghua University, while also transferring the stewardship of the Cultural Revolution over to the workers. The factory workers saw the refuted mangos as a great sacrifice on behalf of Mao for his workers, and Mao subsequently appointed the factory workers the permanent managers of the country’s education system, in a shocking but typical display of China’s reverse credentialism. The workers went back to their factories, with each of the factories that had contributed workers to the defense of Tsinghua University being given a mango. These mangos would become sealed in wax, put in glass contained, and began to take on a religious reverence among the workers of China, who saw it as a personal gift from on high. People were issued mango replicas made out of plastic and wax, while traveling mangos were sent around the country, accompanied by grand processions full of fanatics that traveled from village to village, showing off to everyone the single mango that they carried with them. It became counterrevolutionary to even question the magnificence of the mangos, with a story of a village’s dentist, Dr. Han, opining that the mango just looked like a sweet potato. Dr. Han was declared guilt of blasphemy, tried for treason, and after being found guilty, was paraded throughout his village. The mango worshippers put Dr. Han on the back of a truck, driving him out to the edge of town, before executing Dr. Han via shot to the head. This was a common occurrence during the latter days of the Cultural Revolution, and serves to give you an idea of the sheer insanity that was engulfing China. Unlike in the Soviet Union, where you could pull a Jeffrey Epstein on Stalin’s daughter and survive, in China if you didn’t worship a mango your life was in peril.

China had a serious problem, in that its economy was in tatters, its political climate kept the regime afloat through the utilization of violently fanatical devotees, and that it was slipping into irrelevance on the international stage. Mao needed a friend, and when America saw an alliance with China as essential to driving a divide inside the communist camp, Mao’s regime found new support in the least expected place. While Kissinger landed in China in secret and met with officials in 1971, Nixon arrived in China in 1972, formalizing relations between the countries. Mao saw in America the potential for an alliance that could throw off the dominance that the Soviets held over the socialist camp, and as trade relations gradually began, America’s corporate executives jumped on the opportunity to offshore and outsource their unionized labor force. America helped China greatly in this regard, allowing American businesses to write off the expenses associated with building factories and other facilities within China, going so far as to give tax breaks to businesses that moved their production operations to China. Similarly, a shipping agreement was reached between America and China, with America offering large discounts from 40 percent to 70 percent on Chinese goods shipped to America. For almost half a century until the shipping subsidies came to an end in 2018, it was cheaper, in terms of shipping costs, for an American to buy a face cream from China, rather than from Los Angeles. In America, the Chinese Communist Party found a way to reinvigorate their economy, giving life to what was a formerly collapsing cesspool and allowing them to explore a new form of market socialism; one in which the CCP’s members could enrich themselves. In China, the bourgeois leadership of America saw a way in which they could further fight communism, while enabling their own domestic industries to disrupt the monopolies that unions held over the workforces there, helping to put an end to American syndicalism.

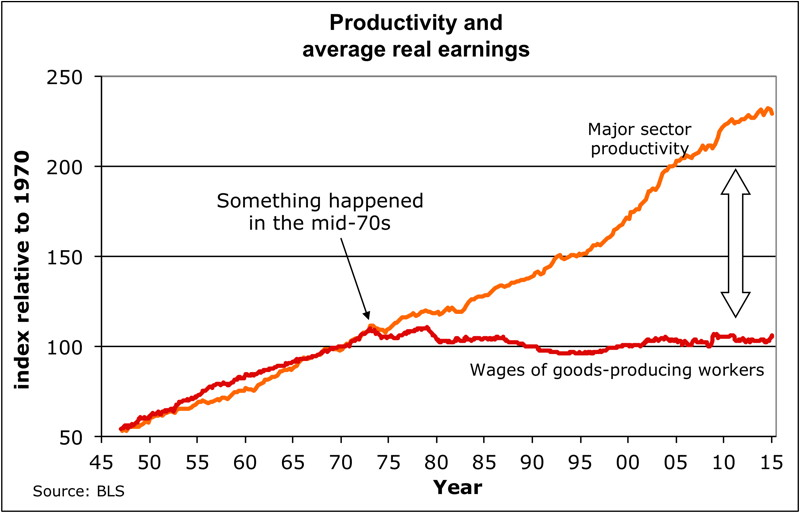

The working class in China lost the material guarantees that came with state employment, often being crammed like sardines into sweatshops where the windows were lined with suicide nets. The working class in America lost the material guarantees that unionized domestic industries offered them, finding themselves unemployed for long periods and shifted into lower-paying jobs without healthcare, without pensions, and without job protections. The rise of Chimerica meant that both the proletariat of China and America experienced economic insecurity on a scale never seen before, as workers were pushed harder and faster to produce more and more. In America, there is a common question asked among people who wonder about the separation in labor productivity and wages that occurred in 1971, as exemplified by this graph:

Many on the right in American politics like to attribute this to our movement away from gold-backed currencies during this time, but this solution they provide for this question has one problem: Gold is not connected at all in terms of commodity prices to the productivity of industries and this separation between wages and productivity didn’t occur in similarly developed countries seen in Western Europe, as well as in Australia or Japan. The reason that this detachment between earnings and output occurred was because, unlike previous decades in history where Americans enjoyed a monopoly over their labor, this was no longer the case. The American proletarians had their hard-fought victories erased by a new market landscape, in which organized labor in many industries proved incapable of competing in terms of profitability with their enslaved Chinese counterparts. This was not a new problem in proletarian economics, with the Roman middle class having disintegrated two millennia before when the super rich’s slave plantations began to produce all of Rome’s wares in their primitive factories and workshops. The beauty of this head-scratching is that, despite all the thinking on the subject, American capitalists couldn’t wrap their heads around the fact that it wasn’t the American workers’ manifest destiny to only grow richer and richer as time went on. Sometimes, capitalism doesn’t work out for your ethnic group., and for nationalists that believe in capitalism, this is an existential threat to their worldviews.

The successors to Mao Zedong embraced capitalism with Chinese characteristics, retaining their communist party in an attempt to safely transition their country into a whore for foreign corporations, were far more enthusiastic than Mao in pursuing economic growth through trade with America. In the following years, the Chinese economy exploded in size in tangible ways, as the vast population found employment in sprawling factory complexes throughout the country. With the collapse of the Soviet Union and its satellite states, China won the cultural war with the Soviet Union, becoming the foremost leader in the crumbling shell of the communist world. China gradually converted to a mix of feudalism and national socialism in their leadership’s attempts to monopolize capitalism in China, doling out favors and privileges to one another as they set up a neo-feudal system where party connections determined wealth. China continued to grow and grow, sometimes at a rate of 10% a year as the West continued to outsource its domestic manufacturing industries to China. Again and again, China’s leaders were little more than capitalists in communist sheep’s clothing, encouraging the growth of trade with America in order to cement their political rule, and thus their wealth in China, by ensuring through policies that focused on maximizing economic growth at any cost that they could keep their citizenry content. The years of resorting to the practices seen in the Cultural Revolution, as the explosion in living standards ensured that China’s political elite did not have to rely on the crazy whims of fanatics to secure their rule, were over. China remained in the background on the Western political stage, happy to silently benefit from their parasitic relationship with the West, but as China has continued to grow and grow, as they’ve found themselves competing with other countries in Asia willing to work for cheaper, their approach to international politicking has changed as well. While China was a tumor on Western capitalism, it coexisted happily with the West during this time, but just as China has come to encounter manufacturing competition with their neighboring countries, China has also found that they’re approaching the size at which they’ll outgrow the West’s ability to sustain their export-driven economy. The tumor of China has reached critical mass, at which point its ability to parasitize off the greater body of the global economy is being challenged by both its own size and the competition of its neighbors.

Unlike Developed Countries, who’s innovation comes from research and development, China’s innovation has always come off of the backs of Western scientists. Unlike Developed Countries, who’s economic growth comes from the activities of their own people, China’s economic growth has always come off of the backs of Western workers and consumers. The fact of the matter is that China has ridden off the productivity of Western capitalism for decades, undergoing liberalization in the 90’s and 00’s when it seemed like there was no end in sight to the gravy train. The regime didn’t have to care about reigning in the economy and forcing their views on the people during this time, because things were by and large getting better and better to the point that there was no threat to the status quo. When Xi Jinping took power, it was a result of the Chinese Communist Party coming to realize that as their economy exploded in size, they could no longer rely on being the bottom-feeder of the global economy. This was partly because, despite China’s attempts to suppress their proletarians’ wages, they haven’t been able to suppress the rising costs of living that come with living in an increasingly advanced economy. It’s cheaper for workers in other countries to do the same work that China can do, yet China has not and potentially never will reach the point at which they can transition into a consumer economy due to their low GDP per capita and very unequal distribution of wealth. This unequal distribution of wealth, in a one-party state where 90% of the richest people in China are members of the CCP, will never and can never be addressed. Ignoring the economic bubble, even if everything was peachy in China and there were no looming debt crises, China is still arriving at a dead-end in terms of economic growth. While it’s easy to take your GDP from $118.70 per capita to $12, 556 in the span of 50 years when the West continues to use you for lower-skilled and less-profitable industries, it’s monumentally harder to go from $12,556 to even $30,000 when your economy is largely built on vacuuming up the crumbs of the Developed World. China has no room to grow but in addition to that, has allowed itself to become overleveraged in terms of debt that we haven’t seen since the Japanese economic bubble.

China faces a very serious debt crisis today, that will require their government to use some force to crack down on people. We’ve already seen this with the recent attacks on bank protestors in China, where some state banks have gone bankrupt and refuse to reimburse their depositors. The real estate industry in China, which is roughly 30% of the Chinese GDP and has seen the creation of countless uninhabited ghost cities, is due to implode in the next several years. Xi Jinping was originally put into power with the idea of countering America’s attempts to stop the spreading of Chinese influence, but now has to focus on things more domestically, as the export-driven economy has begun to crumble in the face of speculation, debt, and declining trade relations with the rest of the world. China’s refocus on domestic affairs, as well its promotion of government power once again in the face of daunting economic odds, is no coincidence but rather a calculated maneuvering by the party to consolidate state power before the economy begins to unravel, cementing their existence into the next phase of China’s economic evolution. Due to the fact that China has less to gain from friendliness with the rest of the world, they’re beginning to engage with the rest of the world in a way which legitimizes their increasingly tight rule at home. Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan, where the Chinese threatened to blast her out of the sky, are an example of this aggressive posturing, helping China to drum up the support of nationalists domestically as their economic prospects continue to fade. In China, no longer can the economy do the convincing for the general public, and so this era of anti-American militarism has begun, in order to secure the confidence of the population by beginning to project their problems on external forces as dictatorships often do. The breakup of Chimerica began when China stopped being small enough to continue being America’s sidekick and Chimerica will continue to sputter away, as the two countries pull apart as the mutual benefits of their alliance vanish more and more.

The American proletariat are unlikely to recover, as supply chains are being simply reoriented towards friendlier and cheaper countries elsewhere. The Chinese proletariat are unlikely to recover, as their employers lose demand for their goods and trade relations continue to worsen to the extent that China’s export economy has few buyers left. Chimerica benefitted the bourgeois of both countries, and in the wake of the breakup of Chimerica, it seems that the Chinese bourgeois are looking to consolidate their political power amidst a looming crisis, while the American bourgeois are simply adjusting their business strategies and relocating resources to other cheap countries who are happy to be whores for foreign corporations. While Chimerica allowed America to benefit from an import-economy and China to benefit from an export-economy, it seems that with the ending of this relationship, America will transition reasonably well, while China will not. Looking back with clear hindsight, it seems that the Soviets made the mistake of utilizing personality cults to build up allies in other countries. In every Soviet-sponsored dictatorship, sluggish growth, nepotism, corruption, and repressive police forces have forced the population to endure a hellish nightmare. Had it not been for trade relations with America, China wouldn’t be any different than Cuba today except in scale. With China returning to its roots, and by that I mean the roots that we saw in the Cultural Revolution, as we see with the pandering to nationalists today, as well as with the Great Leap Forward, as we see in the fruitless megaproject of the Belt and Road Initiative, it can be said that nothing really changed besides geopolitics for a little bit. It goes to show that you can inject all the money into a system that you want, but as long as the system retains its structure and defining characteristics, not much will ever change unless the system in question is replaced. Perhaps China’s greatest contribution to the world is that it showed how a communist party can be composed of billionaires and not be raked over the coals for that in a country it controls, while showing the west that capitalists don’t have any preference for them and that where wealth accumulates in the global marketplace is all circumstantial.